Text Editor Data Structures

Text editors can be an interesting challenge to program. The types of problems that text editors need to solve can range from trivial to mind-bogglingly difficult. Recently, I have been on something of a spiritual journey to rework some internal data structures in an editor I have been building, specifically the most fundamental data structure to any text editor: the text.

Table of Contents

Resources

Before we dive into what I have done here it is important to call out some very useful resources I found for building your own text editor:

- Build Your Own Text Editor - Probably the most fundamental text editor from scratch blog post I’ve seen. This is an excellent tutorial if you are looking to get started on creating your own text editor. It’s worthwhile to note that the editor in this tutorial uses, essentially, a vector of lines as its internal data structure for text.

- Text Editor: Data Structures - A great overview of several data structures that one could use when implementing a text editor. (Spoiler: at least one of these will be covered in this post)

- Ded (Text Editor) YouTube playlist - This is a fantastic series in which @tscoding goes through the process of building a text editor from scratch and served as the inspiration for me going down this rabbit hole in the first place.

Why?

If there are so many good resources out there for building your own text editor (let’s also ignore the fact that there already exists phenomenal text editors today), why am I writing this? There are a few reasons:

- I wanted to push myself into a project kind that I’ve never tried before.

- I wanted to create a tool that I might actually use.

- Building my own data structures have always been something I wanted to tackle more of.

I went through the process of implementing my own data structure specifically because I observed a problem in my program where using something off-the-shelf would not exactly address the concerns I had or provide the flexibility I need. Furthermore, the entire project of writing my own text editor is very much inspired from Handmade Community so everything is built from scratch. If I used an existing solution here I feel it would have been a disservice to the spirit on which the editor is built.

In The Beginning…

I am a strong believer in “experiment and get things working as fast as possible”—essentially, a fail fast mentality. This is not to say that your first pass should ignore optimization, and I refuse to pessimize my code. That said, I started from the simplest possible representation of a text file to start: a giant string.

There are some pretty great properties of having a single string as your text buffer:

- It is the most compact possible representation.

- The algorithms for insertion and removal are simple.

- It is very friendly to the rendering process because you can slice up the string into views which can be independently rendered without additional allocation.

- Did I mention it is simple?

Here’s a short example of insertion and deletion:

void insert_buffer(Editor::Data* data, std::string_view buf)

{

auto old_size = data->buf.size();

data->buf.resize(data->buf.size() + buf.size());

auto insert_at = next(begin(data->buf), rep(data->cursor));

auto end_range = next(begin(data->buf), old_size);

// First splat the buffer on the end, then rotate it to where

// it needs to be.

std::copy(begin(buf), end(buf), end_range);

std::rotate(insert_at, end_range, end(data->buf));

data->need_save = true;

}

void remove_range(Editor::Data* data, CharOffset first, CharOffset last)

{

auto remove_start = next(begin(data->buf), rep(first));

auto remove_last = next(begin(data->buf), rep(last));

auto removed_begin = std::rotate(remove_start, remove_last, end(data->buf));

data->buf.erase(removed_begin, end(data->buf));

data->need_save = true;

}

Note: Yes, the algorithms above could be simplified by just calling buf.insert or buf.erase but the code above just expands the the work that would otherwise be done in those STL functions and do not change the overall complexity.

But, oh boy, do the drawbacks hit hard. If you want to work with any file beyond 1MB, good luck. Not only do you really start to feel those linear time operations but if the underlying buffer needs to reallocate after some edits the entire process slows to a crawl as you need to allocate a larger buffer and copy each byte into the new buffer and destroy the old one. It can turn an O(n) operation into O(n^2) randomly.

There is another, more subtle, drawback to using a giant text buffer: how do you implement undo/redo? The most obvious approach would be to have a separate data structure that tracks all of the individual insertions and deletes. Insertions are much easier to track as you can store them as a range of offsets and simply discard them from the original buffer if the undo operation is invoked. Deletions are a bit more tricky, as with the big string approach you really do need to store a small buffer containing the characters which were removed and the offset from which they were extracted. Something like this would work:

#include <cstddef>

#include <string>

enum class CharOffset : std::size_t { };

struct InsertionData

{

CharOffset first;

CharOffset last;

};

struct DeletionData

{

std::string deleted_buf;

CharOffset from;

};

struct UndoRedoData

{

enum class Kind { Insertion, Deletion };

Kind kind;

union

{

InsertionData ins;

DeletionData del;

};

UndoRedoData(InsertionData ins):

kind{ Kind::Insertion },

ins{ ins } { }

UndoRedoData(DeletionData del):

kind{ Kind::Deletion },

del{ del } { }

~UndoRedoData()

{

switch (kind)

{

case Kind::Insertion:

ins.~InsertionData();

break;

case Kind::Deletion:

del.~DeletionData();

break;

}

}

};

but is overly complicated and requires potentially large allocation overheads when deleting large portions of text. There must be a better way…

Investigation

I knew I wanted to solve all the problems that having a single giant text buffer had, so my concrete goals are as follows:

- Efficient insertion/deletion.

- Efficient undo/redo.

- Must be flexible enough to enable UTF-8 encoding.

- Efficient multi-cursor editing.

Gap buffer

I initially started going down the path of a gap buffer. The gap buffer is very simple to implement and Emacs famously uses a gap buffer as its data structure. A gap buffer would address the first point quite well for isolated edits. It’s not very common that I am editing all over the file all at once, is it? Well… Not quite. One of my favorite (perhaps gimmicky) features of modern text editors is multi-cursor editing (sometimes called block-style edits, though block-style editing is slightly different) and after reading “Gap Buffers Are Not Optimized for Multiple Cursors” (which, btw, has one of the best animations I’ve ever seen to describe a gap buffer in action) Chris Wellons thoroughly convinced me that gap buffers are the wrong way to go because multi-cursor edits are important to me.

Gap buffers are also plagued with similar problems as the giant string representation where efficient undo/redo is difficult without lots of extra storage/data structures.

- Efficient insertion/deletion.

- Efficient undo/redo.

- Must be flexible enough to enable UTF-8 encoding.

- Efficient multi-cursor editing.

Gap buffer is out.

Rope

A rope can be a very attractive data structure for text editors. A rope has a lot of nice properties for editing in particular because it splits the file up into several smaller allocations which allow for very fast amortized insertions or deletions at any point in the file, O(lg n). At first glance, it would seem that a rope addresses all of my initial concerns because operations like undo/redo can more easily be implemented in terms of a tree snapshot (or retaining the removed or changed nodes) and multi-cursor editing becomes a much more lightweight operation.

So where’s the catch? Let’s revisit undo/redo for a moment.

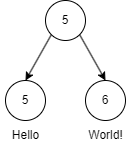

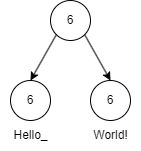

Which represents the string “HelloWorld”. If I want to introduce a space between “Hello” and “World” then the new tree would look like:

Where the node “Hello” was appended with a space at the end. The most attractive version of a rope data structure is to make the entire thing immutable, which implies that when we go to extend the node containing “Hello” we actually end up creating a new node with a fresh buffer to contain the new string or we create a new node just to hold the “ “, which seems equally as wasteful (though the rope should define some kind of constant to limit the size of each node). Copying the node on write implies that, while your undo stack will contain a lightweight version of the original tree, your newly constructed tree can expand your total memory consumption much more than you might initially think.

For the purposes of my editor, I want something a bit more lightweight.

- Efficient insertion/deletion.

- Efficient undo/redo.

- Must be flexible enough to enable UTF-8 encoding.

- Efficient multi-cursor editing.

Piece Table

Now things are getting interesting. The piece table is a data structure that has a long history with text editors. Microsoft Word used a piece table once upon a time to implement features like fast undo/redo as well as efficient file saving. The piece table appears to check many of the boxes for me.

There is one, perhaps, slight drawback. Due to the fact that the traditional piece table is implemented as a contiguous array of historical edits, it implies that long edit sessions could end up in a place where adding lots of small edits to the same file will cause some of the artifacts we saw with the giant text buffer start to appear, e.g. randomly your editor may slow down because the piece table is reallocated to a larger array. Not only this, undo/redo stacks need to store this potentially large array of entries.

- Efficient insertion/deletion (minus very long edit sessions).

- Efficient undo/redo (minus very long edit sessions).

- Must be flexible enough to enable UTF-8 encoding.

- Efficient multi-cursor editing.

Then, the VSCode team went and solved the problem. Enter piece tree…

Piece Tree

I do not want to rehash everything that was covered in the original VSCode blog about their text buffer reimplementation, but I do want to cover why this particular version of a piece table is so interesting and what I needed to change to fill the gaps.

Edit 6/13/2023: It was pointed out that the VSCode team were not the ones to invent the piece tree. Utilizing a tree to represent the individual pieces was suggested as far back as 1998 in Data Structures for Text Sequences. I merely found the VSCode implementation of the idea proposed in this paper to be of high quality and well-tested.

The piece table that VSCode implemented is like if the traditional piece table and a rope data structure had a baby and that baby went on to outclass its parents in every conceivable way. You get all of the beauty of rope-like insertion amortization cost with the memory compression of a piece table. The piece tree achieves the fast and compressed insertion times through the use of a red-black tree (RB tree) to store the individual pieces. This data structure is useful because its guarantees about being a balanced search tree allow it to maintain a O(lg n) search time no matter how many pieces are added over time.

There was just one tiny piece missing… the VSCode implementation does not use immutable data structures, which means that I will need to copy the entire piece tree (not the underlying data of course) in order to capture undo/redo stacks. So it does have some of the drawback of the piece table, so let’s just fix it! How hard could it be? (spoilers: it was hard).

- Efficient insertion/deletion.

- Efficient undo/redo (almost, a tree copy is involved).

- Must be flexible enough to enable UTF-8 encoding.

- Efficient multi-cursor editing.

My Own Piece Tree

The primary goal for implementing my own piece tree was to make it a purely functional data structure, which means the underlying view of the text should be entirely immutable and changing it would require a new partial tree.

The piece tree that VSCode implemented uses a traditional RB tree. After digging out my copy of Introduction to Algorithms book again I quickly realized that trying to reimplement the RB tree described in the book as a purely functional variant was not going to be easy for two reasons:

- The book makes heavy use of a sentinel node which represents the NIL node but it can be mutated like a regular node, except there’s only one.

- The algorithms in the book make heavy use of the parent pointer in each node. Parent pointers in purely functional data structures are a no go because a change anywhere in the tree essentially invalidates the entire tree.

Somebody had to have implemented an immutable RB tree, right? Turns out… yeah? Kind of? In my search I found Functional Data Structures in C++: Trees by Bartosz Milewski in which he covers a simple way to implement a purely functional RB tree, but only for insertion. Insertion is essential to have but I also need deletion, I have to have deletion otherwise the piece tree simply will not work. In the comments it was discussed that deletion is hard, very hard, and that often you need a new node concept to even handle it. I really liked the approach Milewski took for insertion, so I ended up starting my RB tree with this data structure and implemented the rest of the piece tree around it, minus delete but we’ll get to that later.

Where I Diverge

Now that I’m implementing the text buffer as a tree it is extremely important that I design powerful debugging tools to accommodate my journey and evaluate what parts of the implementation need to change in order to solve my specific problems. The original VSCode textbuffer code can be seen here: https://github.com/microsoft/vscode-textbuffer as a stand-alone repo. The real textbuffer implementation (which isn’t really much different from the stand-alone repo) can be seen here: https://github.com/microsoft/vscode/tree/main/src/vs/editor/common/model/pieceTreeTextBuffer.

CRLF

My new implementation of this data structure does not stray too far from what VSCode’s version does. Where I start to differ is in the decision not to codify CRLF line endings as a formal concept in the tree. I don’t like the workarounds they have in the implementation to account for CRLF to be contained within a single piece and I think it massively complicates the data structure for a feature which only needs to be really accounted for in a handful of scenarios. In my existing text editor (without the new text buffer implementation) I account for CRLF in a separate data structure on the side which records line ranges. If the editor is in “CRLF mode” it will rebuild the line ranges in a way that chops the carriage return when it is followed by a newline character. With my new text buffer I don’t record where CRLFs are at all, I simply account for them if a buffer modification happens which needs to delete both \r and \n or when moving the cursor to retract its position to before the \r if it precedes a \n.

Here’s an example of what the user sees when “CRLF mode” is active and the cursor navigates before/after a CRLF line:

Here’s what the system does underneath to either skip the carriage return or retract to the character before it (the ¶ character represents the \r):

The data structure does not need to record the CRLF due to the limited number of times the editor even needs to consider the carriage return character.

Debugging

Being able to debug a complicated data structure is essential if you intend to make any progress. If you observe the stand-alone repo for the VSCode implementation you will note that the primary way of validating the buffer contents is through getLineContent, which is a fundamental and important API. For the purposes of really confirming the entire buffer I needed a different approach so I designed a tree walker with an iterator-like interface so I can use a for-each loop:

class TreeWalker

{

char current();

char next();

void seek(CharOffset offset);

bool exhausted() const;

Length remaining() const;

CharOffset offset() const;

// For Iterator-like behavior.

TreeWalker& operator++();

char operator*();

...

};

struct WalkSentinel { };

inline TreeWalker begin(const Tree& tree)

{

return TreeWalker{ &tree };

}

constexpr WalkSentinel end(const Tree&)

{

return WalkSentinel{ };

}

inline bool operator==(const TreeWalker& walker, WalkSentinel)

{

return walker.exhausted();

}

This walker proved to be invaluable for validating edits and deletes and opened up a lot of extra room to ensure that UTF-8 support was correct since I needed the ability to walk specific codepoints at a given offset. Naturally, the other debugging tools that follow are a way to print the tree nodes themselves as well as the associated pieces:

void print_piece(const Piece& piece, const Tree* tree, int level);

void print_tree(const Tree& tree);

Undo/Redo

The VSCode implementation did not implement undo/redo directly as a text buffer operation, they did it through a system in which edits applied to the text buffer would record the series of ‘reverse’ operations needed to undo the prior edit and pass that to the caller which was then responsible for storing this information and responsible for applying reverse edits in sequence. This system is certainly one approach and avoids having to copy the entire tree again, but it relies on allocating buffers of data similarly to how we postulated undo/redo could be done with the single string implementation. Here’s my undo/redo routines:

UndoRedoResult Tree::try_undo(CharOffset op_offset)

{

if (undo_stack.empty())

return { .success = false, .op_offset = CharOffset{ } };

redo_stack.push_front({ .root = root, .op_offset = op_offset });

auto [node, undo_offset] = undo_stack.front();

root = node;

undo_stack.pop_front();

compute_buffer_meta();

return { .success = true, .op_offset = undo_offset };

}

UndoRedoResult Tree::try_redo(CharOffset op_offset)

{

if (redo_stack.empty())

return { .success = false, .op_offset = CharOffset{ } };

undo_stack.push_front({ .root = root, .op_offset = op_offset });

auto [node, redo_offset] = redo_stack.front();

root = node;

redo_stack.pop_front();

compute_buffer_meta();

return { .success = true, .op_offset = redo_offset };

}

Yep, that is all you need. Two linked lists and a call to compute_buffer_meta() (which is a O(lg n) operation). When the entire data structure is immutable you can snap back to any root you have previously saved a reference to and the editor state will be completely consistent—which, I will mention, brings up the possibility of creating a UI for branching editor states (like a mini-source control system) where the user could navigate an editor state graph to some state they had previously, no more messy git commit -am'testing' commits to only be reverted later!

Revisiting Deletion

I said I would revisit delete operations because they’re just as fundamental as an insertion operation when talking about text editors. When going down the path of implementing immutable RB tree deletion, I’ll be honest, I nearly gave up several times. The algorithm mentioned in my algorithms book was simply not workable because it needed to be converted into a recursive version where we also somehow eliminate the sentinel nodes (which VSCode’s RB tree implementation uses, but that is not necessarily a bad thing). There is an excellent RB tree algorithm visualizer provided by the University of San Francisco CS department that I strongly urge you to check out if you’re interested in exploring the algorithms in action.

To get some idea of the complications behind why RB tree deletion is difficult we need to peek into the cases that need to be covered by the traditional RB tree deletion. In particular the cases where you introduce a double-black violation by deleting a red node leaves a lot of room for error. Luckily, someone else thought that implementing an immutable RB tree was useful and I found persistent-rbtree which was actually adapted from the Rust Persistent Data Structures. This code had some reliable node deletion logic that I could adapt to my existing RB tree and it ended up serving as the basis for my deletion routine. You can see how it is done in the final repo below.

Finally, after implementing deletion I had my ‘perfect’ data structure (for me):

- Efficient insertion/deletion.

- Efficient undo/redo.

- Must be flexible enough to enable UTF-8 encoding.

- Efficient multi-cursor editing.

fredbuf

It would be crazy of me to get this far and have no code to show for it. ‘fred’ is the name of my text editor and since I have sufficiently modified the VSCode textbuffer and adapted it specifically for ‘fred’ I have dubbed it ‘fredbuf’. You can view all of the code and tests at the repo for fredbuf. It has no 3rd party library requirements so the build is as simple as you can get. It is MIT licensed, so go wild! Improve it beyond what I ever thought possible! The repro just requires a C++ compiler that supports C++20. Perhaps I’ll release ‘fred’ one day too.

Conclusion

What did I learn from this?

- Doing research and identifying the constraints up-front is absolutely essential. You don’t want to waste time finding out that a complicated data structure won’t solve your problems after you go through the pain of implementing it.

- Create debugging utilities for data structures very early on. I doubt I would have completed this project if I had not created powerful debugging utilities from the start.

- Immutable RB tree deletion is hard

.

.

If you’re also interested in text editor design, the C++ language, or compilers have a chat with me over on Twitter. I’m always interested in learning and sharing any knowledge that could prove to be useful to others.

Until next time!