Mapping Strings in C++

Mapping strings to things makes sense. You take a meaningful string and you assign it a value. As with most things we do in programming there are many pitfalls to approaching a problem. So, lets explore some of them!

What Exactly Is Your Problem?

Here’s a situation we’ve all run into at some point.

Say you’re reading records from a database and it has a column called “Type”. Lets say for some reason the designer wanted things to be a little bit human readable so this “Type” column is a varchar(30). When you read this string in you need to parse it into some internal type within your application.

What method do you use?

std::vector<std::string> and use the index as your enum type?

std::map<std::string, enum_t>?

std::unordered_map<std::string, enum_t>?

Hey, std::vector is fast!

And indeed you would be right! Of all the STL containers std::vector is by far the most used, tested, and fully understood container to ever grace C++. What it isn’t is a Swiss Army Knife. But lets use it like one anyway!

Consider this:

enum class types_t : std::size_t {

circle,

square,

triangle,

num_types

};

// initialize size == num_types

std::vector<std::string> v(static_cast<std::size_t>(types_t::num_types));

auto convert = [](types_t t) -> std::size_t { return static_cast<std::size_t>(t); };

v[convert(types_t::circle)] = "circle";

v[convert(types_t::square)] = "square";

v[convert(types_t::triangle)] = "triangle";

With this you can now lookup your internal type like so:

// returns type_t::num_types if failed

auto get_type(const std::string& type) {

return static_cast<types_t>(std::distance(

std::begin(v),

std::find(std::begin(v), std::end(v), type)));

}

I understand this is an extremely naïve implementation but the concept is there. We use strings in order to obtain a handle to some internal type.

Don’t worry we’ll get to benchmarks and how we can make this particular implementation faster.

But Why Not Use std::map?

Good question. Let’s use one:

// using same 'types_t'

std::map<std::string, types_t> m;

m["circle"] = types_t::circle;

m["square"] = types_t::square;

m["triangle"] = types_t::triangle;

Well that was easier. What does the request to get the type look like?

auto get_type(const std::string& type) {

auto e = m.find(type);

if (e == std::end(m)) return type_t::num_types;

return e->second;

}

OK so that looks a little easier to read and if we have a ton of types we won’t exactly do a linear search due to the way std::map stores its entries (using RB trees).

std::unordered_map follows the same rules as std::map the only difference is that when you want to request all of the types from it the resulting list is unsorted. This behavior does have some performance implications and tells us a little bit about std::unordered_map stores its elements (probably using buckets and separate-chaining to handle collisions).

Lets See Some Numbers!

Right, so you’re probably tired of hearing me ramble about silly implementations of different things string storing techniques. Lets compare some.

For this test I generated random strings all between the lengths of 10 and 100 so we can observe strings outside of SSO (Small String Optimization)

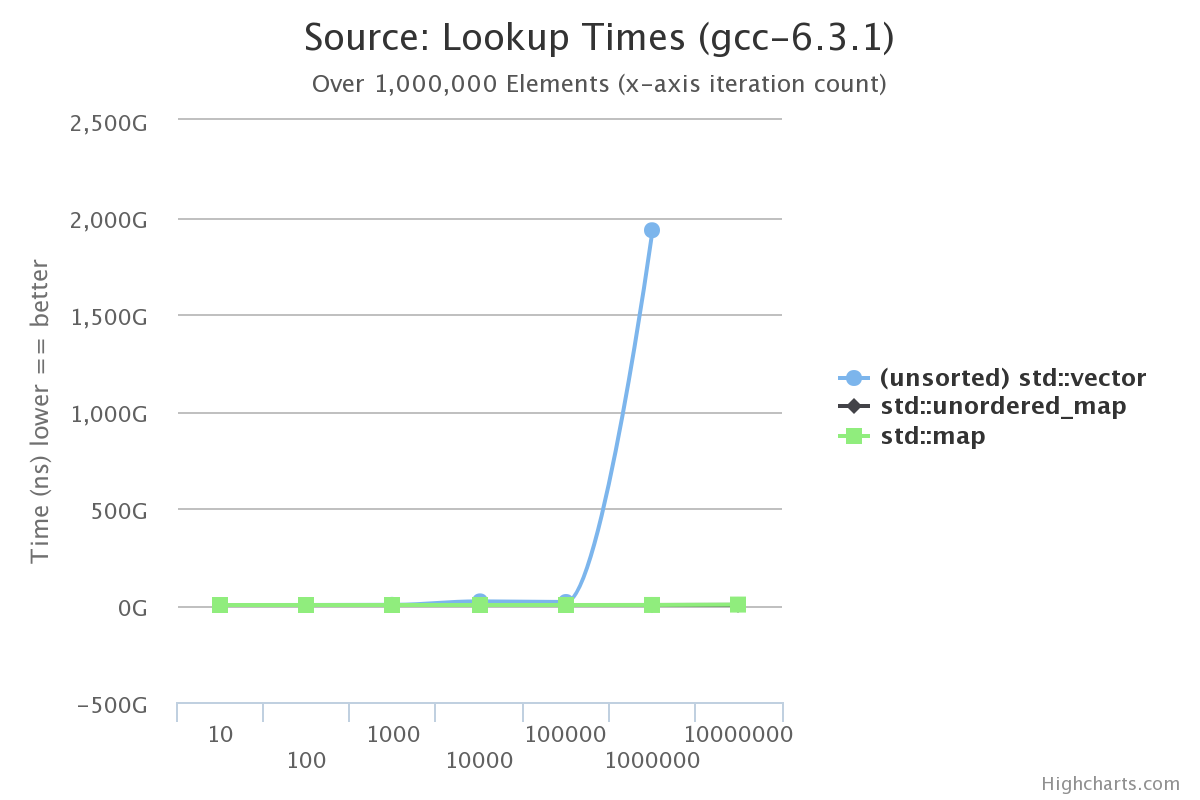

So… That’s less than helpful. At around 1,000,000 elements our unsorted vector takes around 32 minutes to lookup a string.

Let’s fix this. An easy way to get our std::vector implementation in-line with the rest of the containers is we can sort it and utilize an algorithm, std::lower_bound, in order to speed up our lookup times.

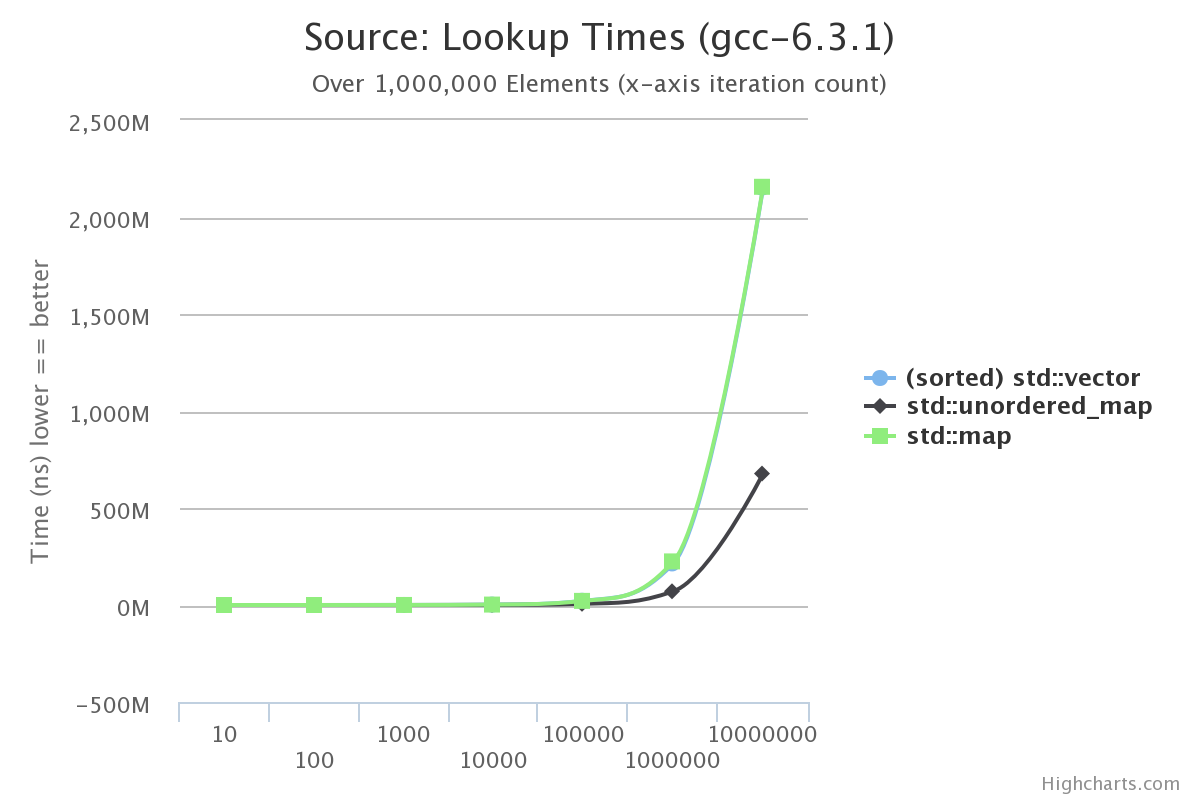

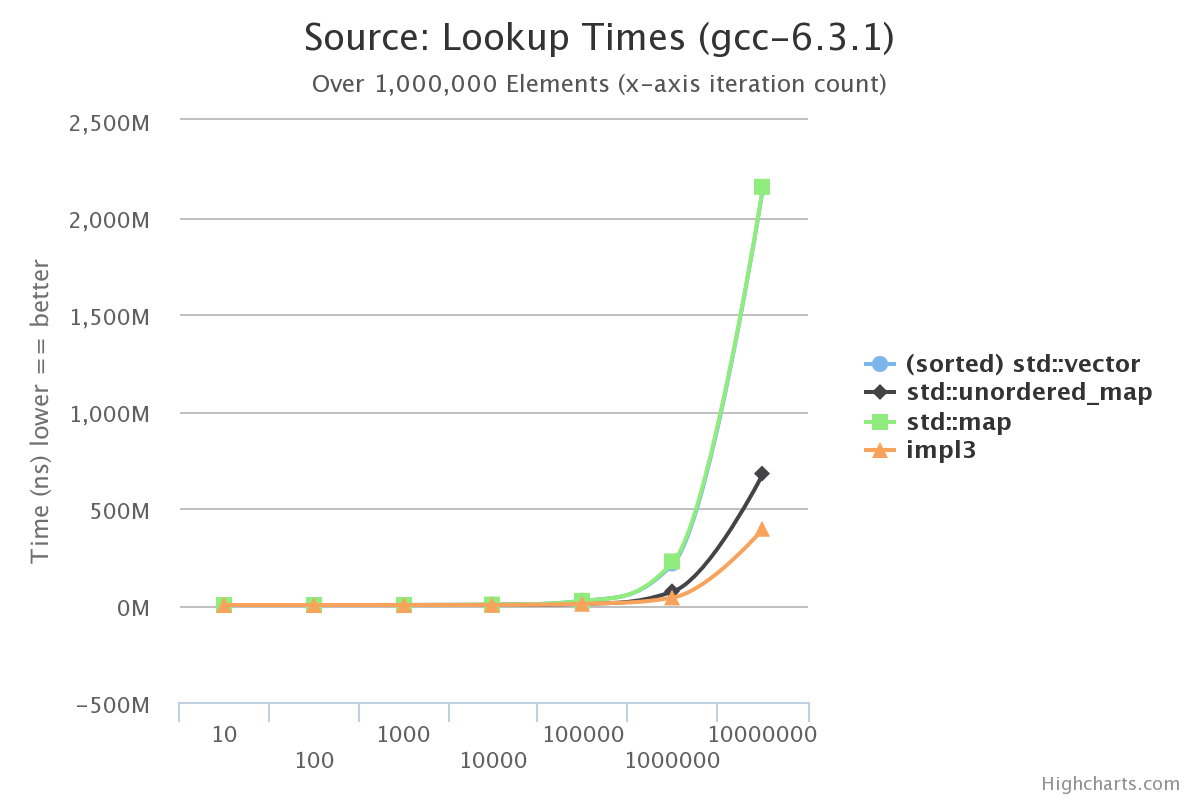

Lets see how that change affects the benchmark:

These are much better numbers. We can actually see std::vector basically even with std::map while std::unordered_map starts beating out both.

There Might Be A Better Way…

If you think about the problem we’re actually solving here you could actually relate it to another common problem of pattern matching in search engines.

In our problem we have a finite set of things that a string could match to. With that in mind we can short cut a lot of the matching process if we manage to find a string with a certain prefix.

For example, in the list of strings ["cat", "cake", "bat"] if we have the prefix "ca" then we have two potential matches, "cat" and "cake", however if we have a prefix of just "b" then we don’t even have to compare the rest of the string to "bat" to have a full match, we can just take "bat". This, of course, is all under the assumption you can short circuit like that in your string match. It’s possible you have malformed type strings. Keep this in mind when considering the following solution!

Luckily there is a data structure that will do just this type of prefix matching. A Trie.

The Trie

Many may know what a Trie is but for those who don’t it is a tree based structure that is optimized for matching string prefixes to words inserted into the tree.

Conceptually:

This is the resulting structure after we insert the words "ask", "as", "bake", "bat", "cat" and, "to"

An extremely simple implementation of this structure uses a std::map to place a char leading to another node in the tree. Nodes can then be annotated with whether or not they’re a word (since individual branches can also be words in the case of "as" above).

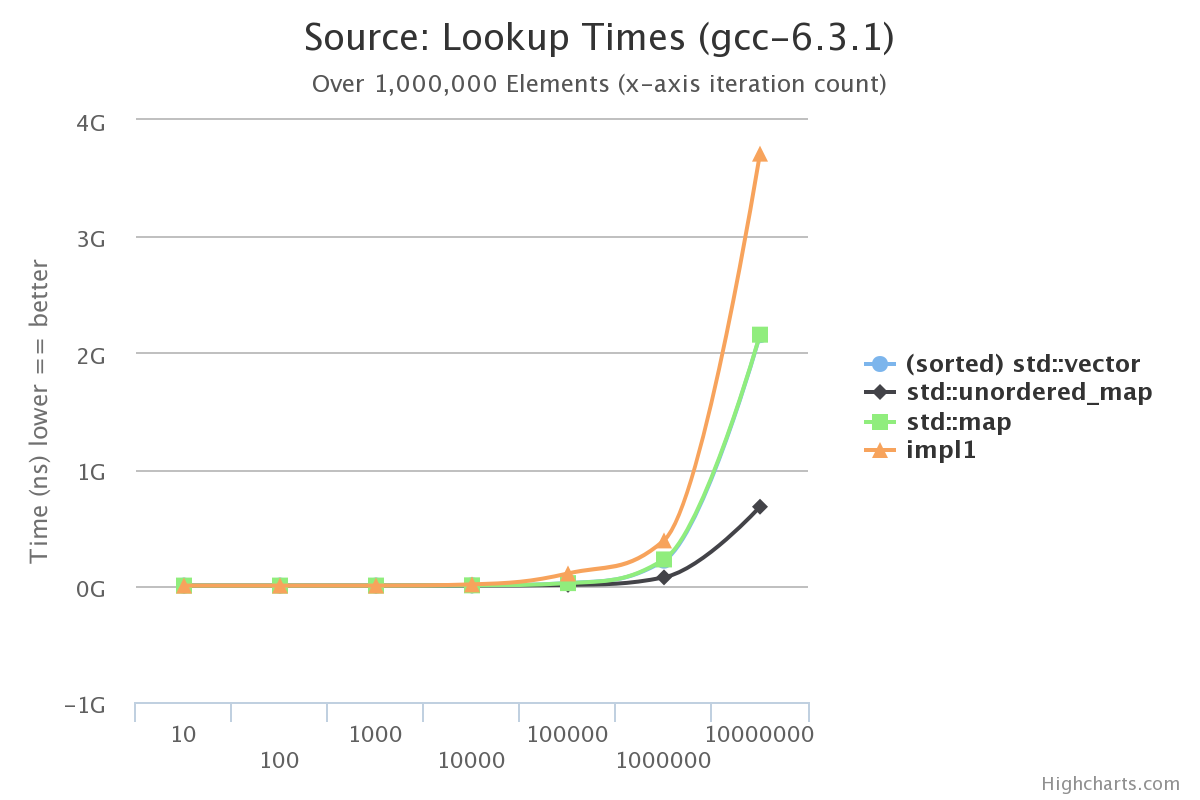

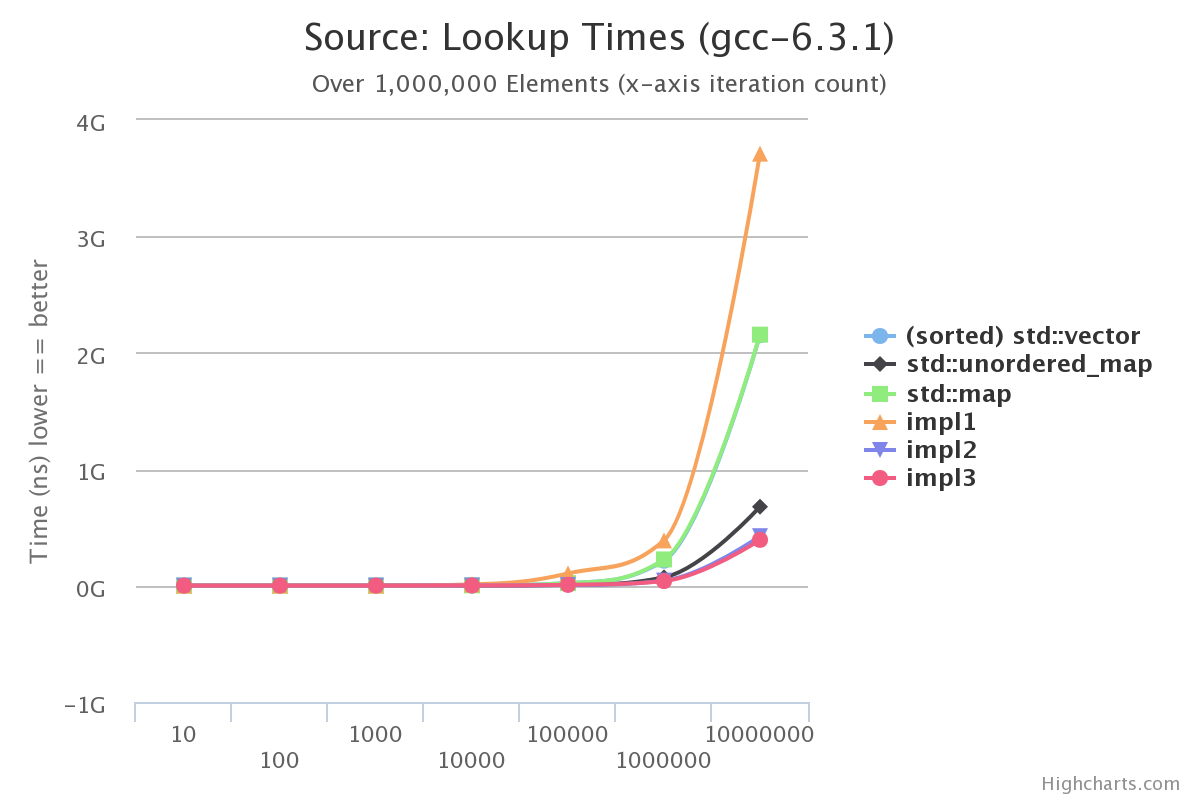

Lets see how this implementation might compare to our existing benchmarks:

OK, so with the naïve implementation we don’t even beat std::map. This is unsurprising because it uses std::map under the covers to maintain the Trie invariant of being sorted. We want to maintain that the Trie is sorted so we can return sorted lists of words, so we won’t bother using std::unordered_map to implement the node behavior.

Improving Trie

All this said, there is a lot of room for improvement. Mainly in the way we store words that are leaves. If you’ll notice, whenever we created the subtree for "bake" we added an extra branch node between where the leaf and the end of the word. This problem is exacerbated when we have very long words with no common prefixes with other words in the tree.

In essence the tree has two different types of nodes: leaf nodes and branch nodes. Leaf nodes are those that only contain the full words and branch nodes have child nodes that are either leaves or more branches. Here, I chose inheritance to do the trick for me:

struct node_concept_t;

struct branch_node_t : node_concept_t;

struct leaf_node_t : node_concept_t;

To determine if I was at a leaf or branch I used the visitor pattern to tell me the information I needed.

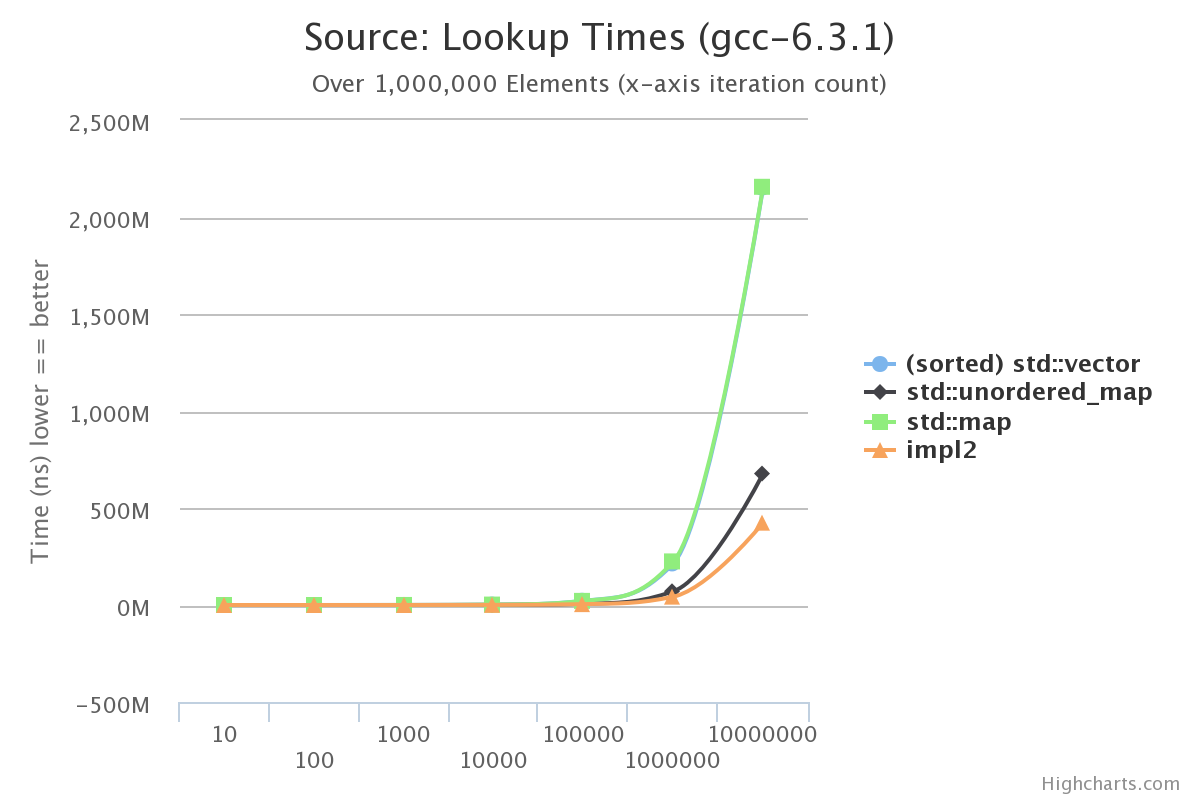

Lets see how this implementation stacks up:

This is looking promising! This implementation even beats std::unordered_map in terms of lookups. The reason we start to edge out std::unordered_map is because this structure is allowed to shortcut longer string comparisons by binary searching and has a decent memory layout when inspecting leaf data.

So I Kinda Lied…

impl2 doesn’t quite have what we need just yet. It can’t actually store values. It only looks up strings. So the final implementation, impl3, will store values and has yet another neat feature.

In impl2 branch nodes were annotated via a boolean variable to indicate whether or not it was word. Just like in the naïve implementation, impl1. In impl3, however, we take a different approach. We distinguish branches that carry values with a type of their own:

template <typename>

struct node_concept_t;

template <typename>

struct branch_node_t : node_concept_t;

tmplate <typename>

struct branch_value_node_t : node_concept_t;

template <typename>

struct leaf_node_t : node_concept_t;

Notice we also templated each type in order to store the values in leaf and value branches. How does this implementation fare?

Good! We’re still beating out the std::unordered_map implementation even while storing values!

Bringing It All Together

Now that we have all the information, lets see how it all looks:

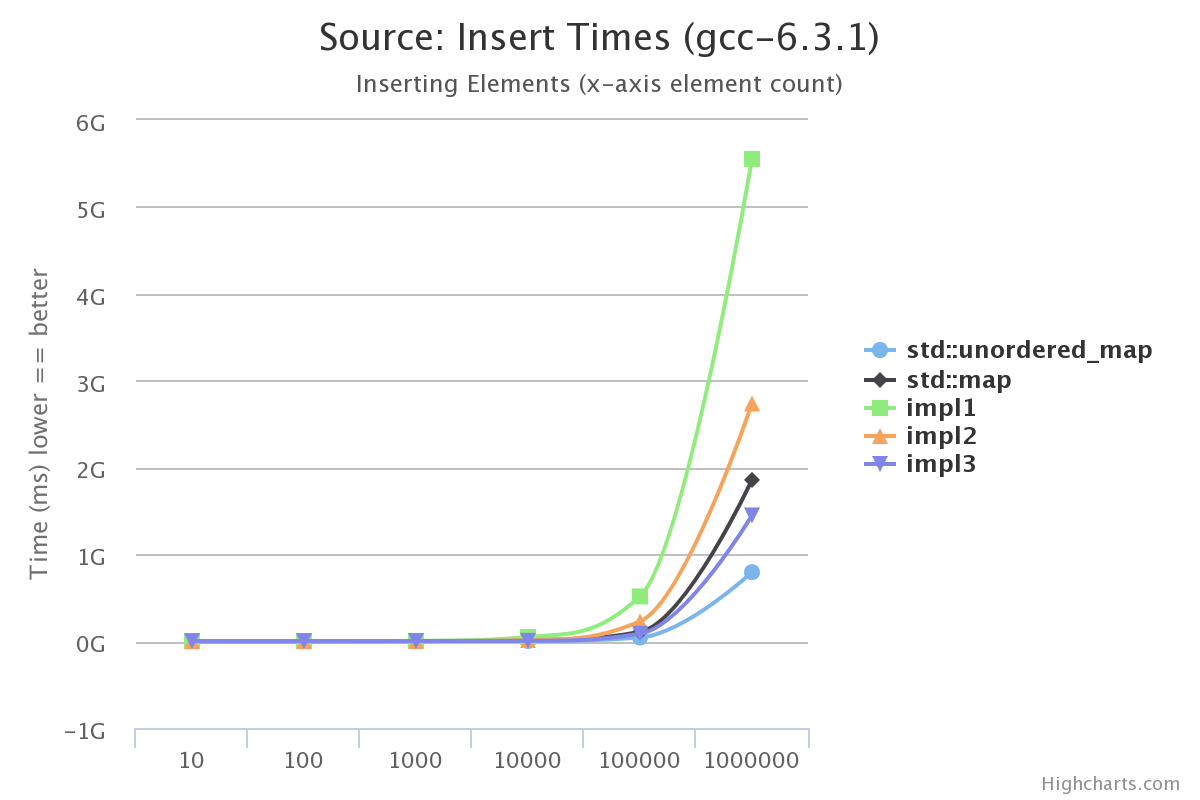

It’s not enough to just benchmark lookup times, insert times are a concern too. Here’s a benchmark of inserting various numbers of elements using the same parameters (words between 10 and 100 characters in length):

Here it’s pretty expected that std::unordered_map beats impl{1,2,3} since its insert time only occasionally rehashes the whole data set. Generally the hash is linear in complexity, making the total insert time O(n + k) where n is the string length and k is (potentially your chain size). In our Trie we need to do a prefix match and potentially breakup a leaf node into multiple branches and up to two other leaf nodes. This makes our insert time on the order of O(n lg n).

I encourage you to check out the code where the benchmark code can be found along with the Trie implementations.

A quick shout out to gochart for providing the awesome chart making utility and draw.io for the Trie visualization.

Until next time!